Parts of a Fish Explained

Have you ever thought about what makes fish such incredible swimmers? It all has to do with their body design. While we commonly call them "fish," these creatures do not actually belong to a single taxonomic group, but rather a diverse collection of aquatic vertebrates that share certain features. Most have transformed their limbs into fins, covered their bodies with protective scales, and developed specialized gills for breathing underwater.

In this guide by thedailyECO, we’ll explore the different parts of a fish, explain what each part does, and help you understand fish anatomy in a simple, visual way.

Body structure

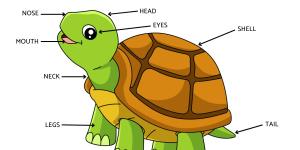

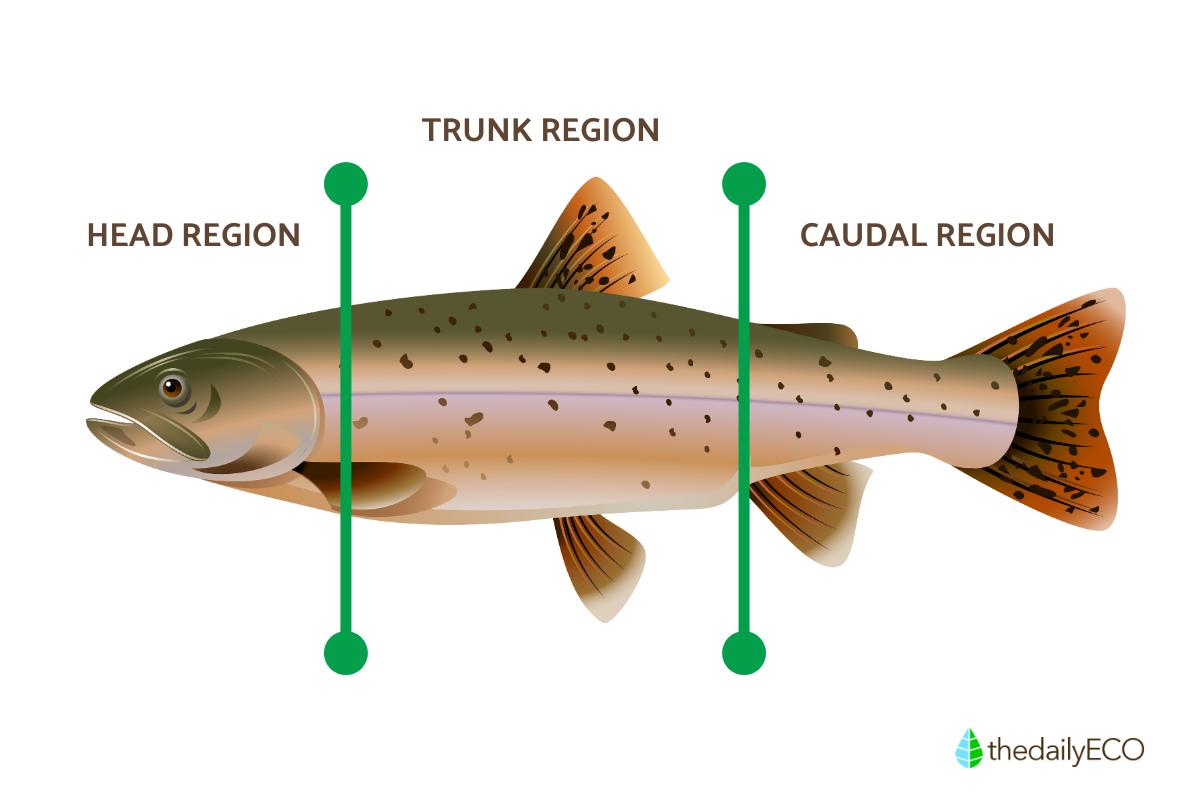

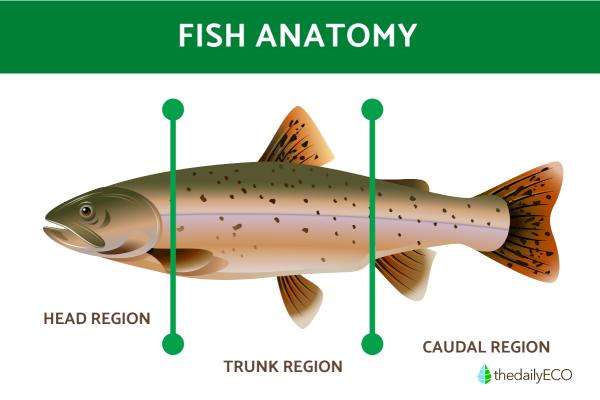

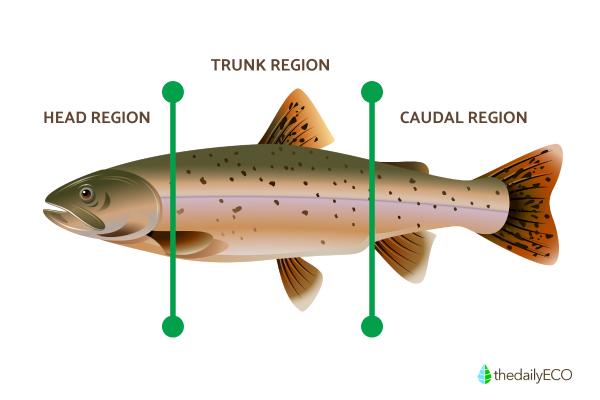

Fish bodies show adaptations developed throughout 500 million years of evolution in water. Their physical structure carefully balances hydrodynamics, buoyancy, propulsion, and survival needs. Most fish bodies follow a standard organization with three main regions:

- Head region: the head contains the brain, major sensory organs, mouth, and gill apparatus. This area processes information from the environment and manages both food intake and respiration.

- Trunk region: this main body section houses vital organs including the heart, liver, digestive tract, kidneys, and reproductive organs. The trunk contains most of the muscle mass used for swimming and includes the swim bladder for controlling buoyancy.

- Caudal region: also called the caudal region, this posterior section consists mainly of powerful swimming muscles and vertebral support structures. The tail generates the main propulsive force that drives the fish through water.

Fish bodies display various shapes related to habitat and behavior:

- Fusiform (torpedo-shaped): this is the most common shape, tapered at both ends for fast swimming in open water. Tuna, salmon, and trout exemplify this efficient design that reduces water resistance.

- Compressed (laterally flattened): thin, tall body shape for maneuvering through vegetation or coral. Angelfish and butterflyfish use this form to navigate complex environments and hide from predators by turning sideways.

- Depressed (dorso-ventrally flattened): flattened top-to-bottom like rays and flounder. This shape allows bottom-dwelling or concealment in sand.

- Anguilliform (eel-like): elongated, cylindrical bodies for navigating tight spaces, crevices, and burrows.

Water is about 800 times denser than air, so fish bodies minimize resistance through streamlining and mucus coatings that reduce friction.

Their movement relies on zigzag muscle fibers called myomeres that run along their bodies. When a fish swims, these muscles contract in a wave pattern from head to tail, propelling the fish forward. Body coverings vary across species, but typically include scales for protection and a mucus layer that reduces friction and provides defense against pathogens.

Head

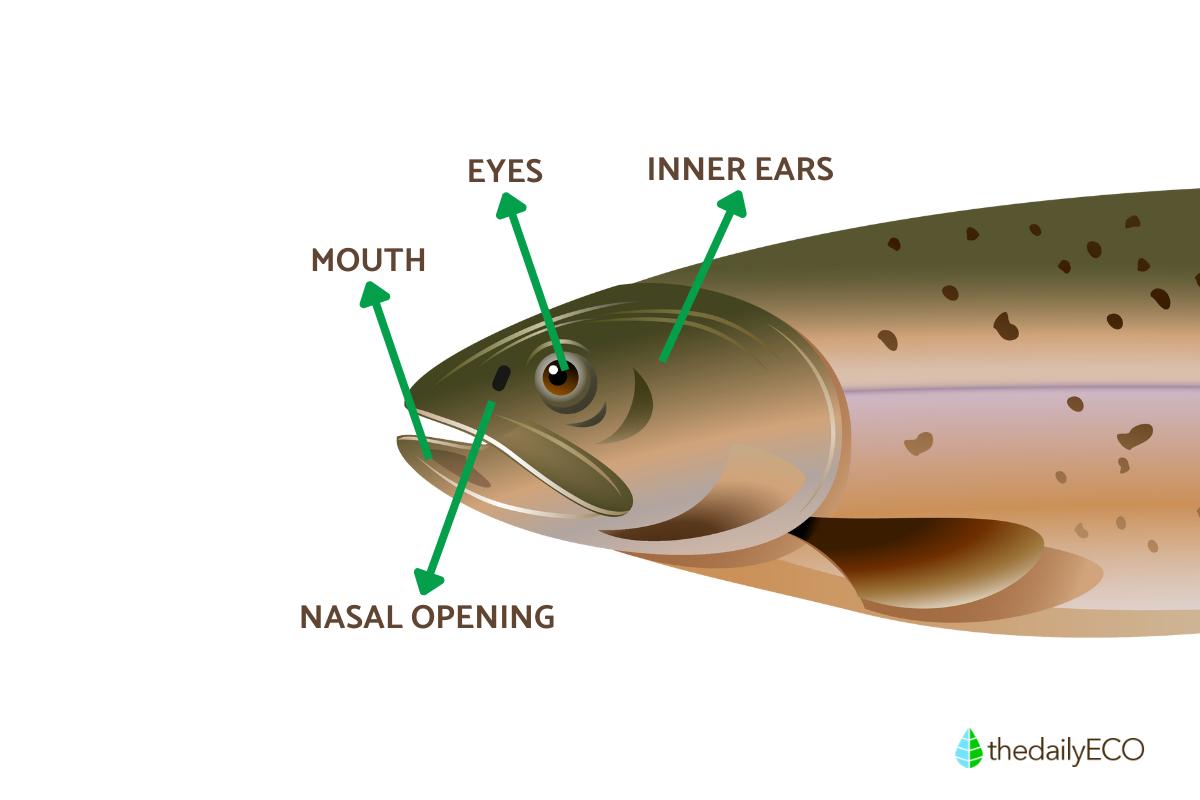

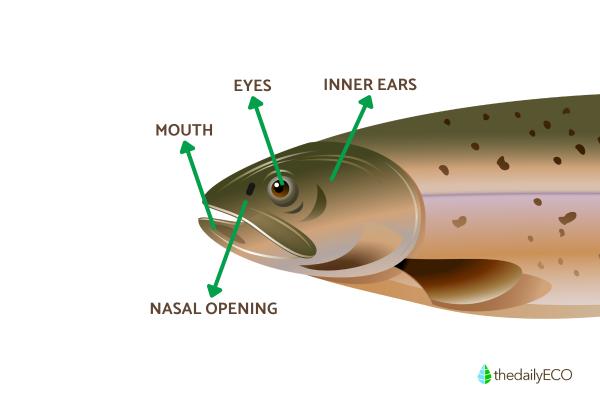

The fish head houses an array of specialized sensory equipment that helps navigate underwater environments:

Eyes:

Fish eyes have no eyelids. Positioned on the sides of their head, these eyes provide a panoramic view of surroundings.

This wide-angle vision gives fish nearly 360-degree awareness, useful for spotting both predators and prey in their three-dimensional aquatic environment.

Inner ear:

Fish have sophisticated inner ears that detect sound and maintain balance. While lacking outer and middle ear structures, their hearing functions effectively underwater.

Some fish species have developed a connection between the inner ear and swim bladder via Weber's ossicles. These are tiny bones that amplify sound vibrations. This adaptation turns their swim bladder into an underwater hearing aid.

Mouth:

Fish mouths reveal their feeding habits. Almost all fish have jaws, but mouth position varies based on diet. A terminal mouth faces forward, perfect for predators chasing prey. A superior mouth points upward, ideal for surface feeders. An inferior or subterminal mouth faces downward, suited for bottom-feeders that graze on algae or hunt creatures in sediment.

Nasal opening:

Fish have nostrils used exclusively for smelling, not breathing. Located at the front of the head below the eyes, these openings connect to sensitive olfactory tissue. Fish have an acute sense of smell that detects minimal concentrations of substances in water. This ability helps them locate food, recognize territories, avoid predators, and find mates.

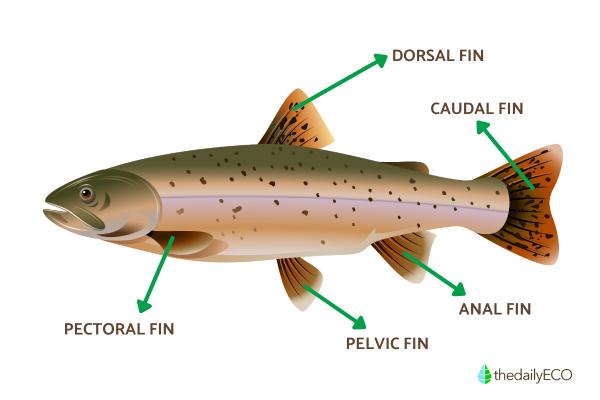

Fins

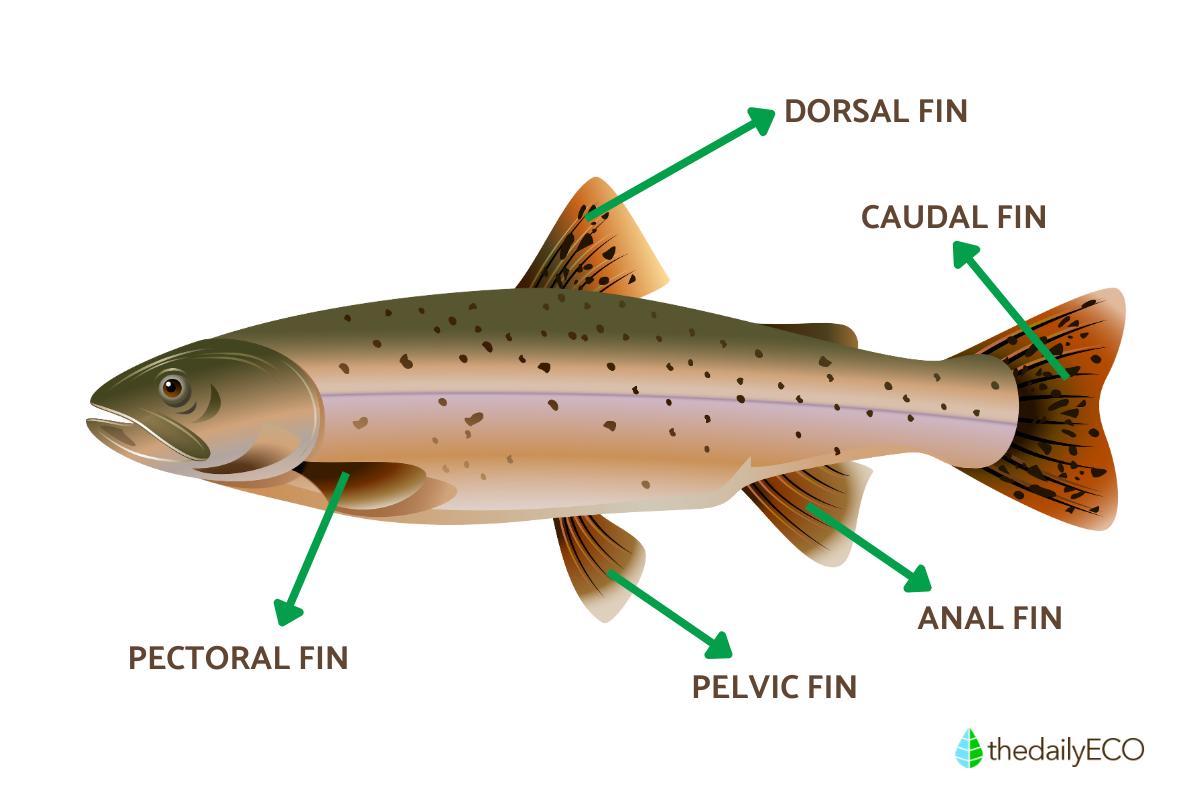

Fish fins are modified limbs covered with a cuticular membrane stretched over supportive rays. Some fins come in pairs while others stand alone.

Most fish have a similar fin arrangement: paired pectoral and pelvic fins (one set on each side) along with single dorsal, anal, and caudal (tail) fins along the top and bottom midlines.

Each fin serves a distinct purpose in underwater movement:

- Dorsal and anal fins: located on the top and bottom of the fish, these vertical fins act like keels on a boat, preventing rolling and providing stability. They help with precise forward and backward movements, allowing fish to maneuver with control.

- Pectoral fins: these side fins function as brakes when extended outward and allow fish to make up-and-down adjustments in the water column. Many fish use these fins for delicate maneuvers, especially when hovering.

- Pelvic fins: positioned on the lower side of the body, these fins provide stability and help fish maintain position near the bottom or around vegetation. They assist with precise control during slow swimming.

- Caudal fin (tail): the primary power source and steering mechanism. With powerful side-to-side movements, the tail generates forward thrust while determining direction, functioning as a boat rudder.

Curious about how those small fry develop into full-grown fish? Dive deeper into the fascinating world of fish development in our other article.

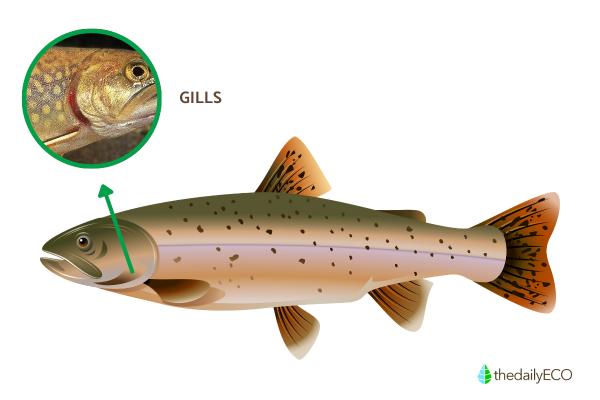

Gills

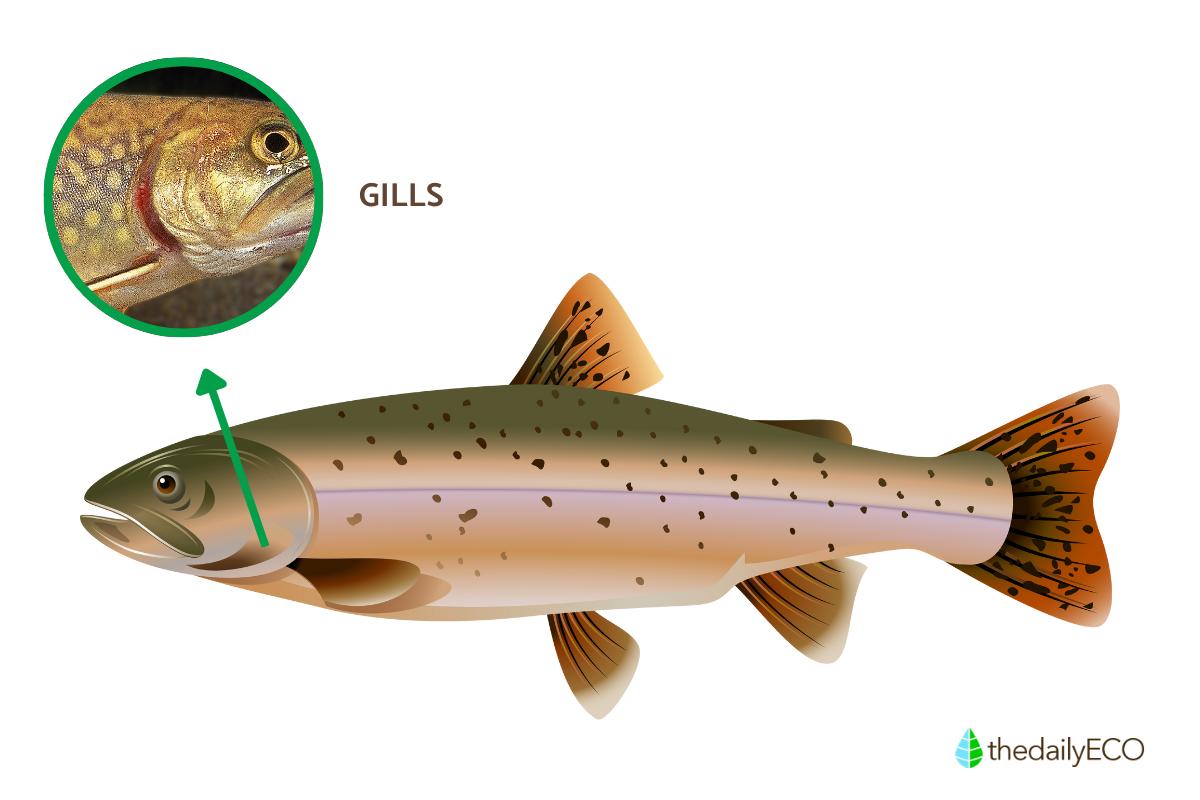

Fish, like us, need to breathe oxygen and release carbon dioxide. However, water contains only 1% available oxygen compared to the 21% in air. Therefore, fish have developed a specialized system for efficient oxygen extraction, this crucial role is fulfilled by their gills.

Gills are thin structures filled with blood vessels and folded to increase surface area. They sit in chambers on both sides of the fish's head and work efficiently, capturing up to 80% of oxygen that passes through them. Most fish have an operculum, a movable flap covering their gills that provides protection and helps create water flow for breathing.

The breathing process works simply. Water enters through the mouth, moves across gill filaments where oxygen enters the bloodstream while carbon dioxide exits, then flows out through openings behind the operculum. This cycle never stops, allowing fish to get oxygen from water continuously.

Some fish, such as lungfish, have developed lungs along with gills. These species can breathe air directly when water becomes oxygen poor or dries up, a key adaptation that helped fish begin the transition to land millions of years ago.

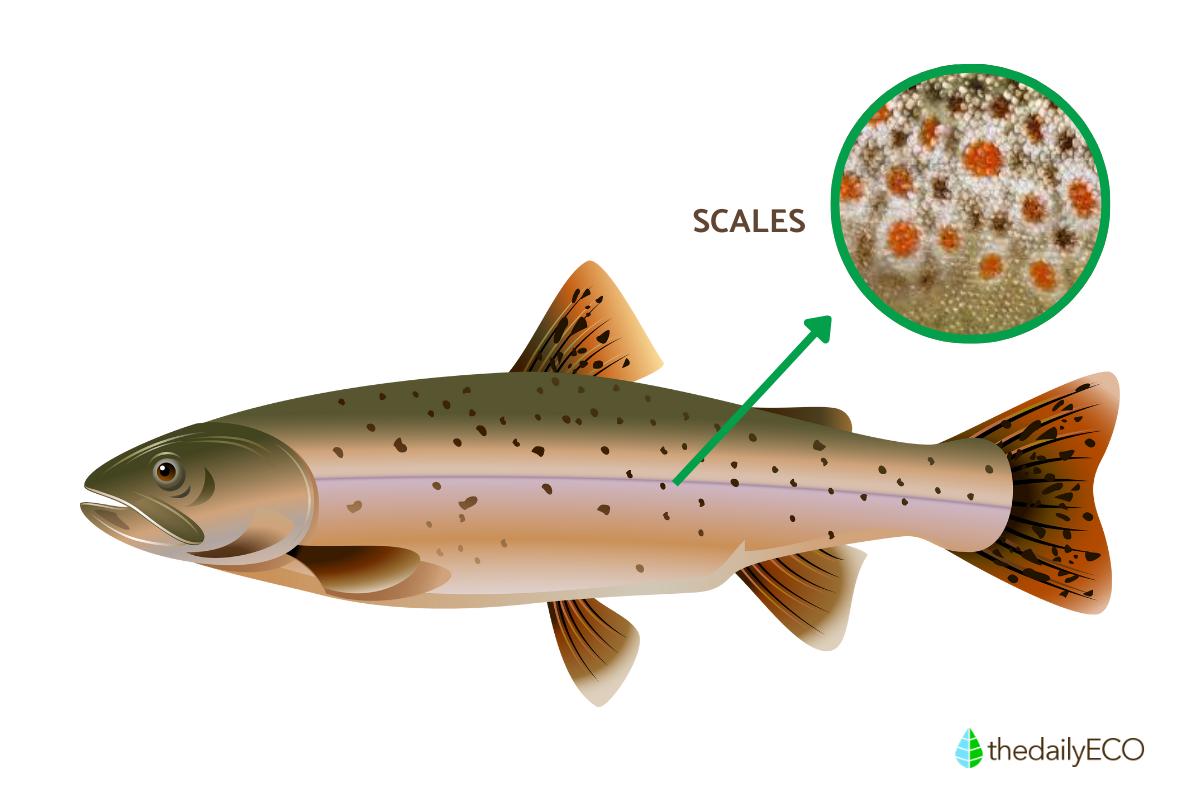

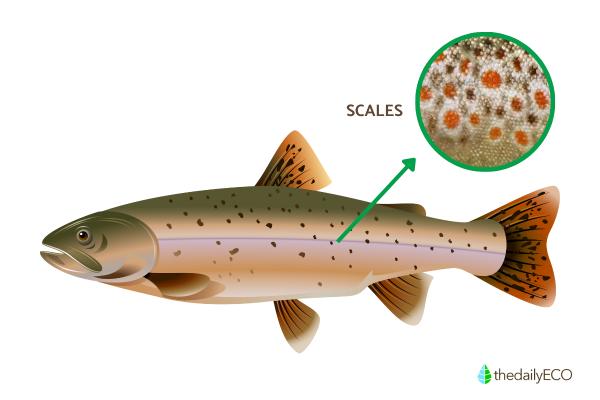

Skin and scales

Fish skin contains mucous glands that secrete a protective substance. This coating acts as a barrier against parasites and pathogens, reduces friction during swimming, and contains antibacterial properties to prevent infection.

Beneath this coating, most fish have scales. Unlike reptile scales, which form from outer skin folds, fish scales develop from deeper skin layers (the dermis) and grow throughout life. This continuous growth creates patterns scientists can read to determine age and environmental conditions.

Fish scales come in several types, each showing how fish have adapted to their environments:

- Placoid scales: found on sharks and rays. These scales feel like sandpaper because they're actually tiny tooth-like structures. They protect the fish and help it swim faster by reducing drag in the water.

- Ganoid scales: these are hard, diamond-shaped armor plates with a shiny coating. Sturgeon and gar have these scales, which protect them from predators but limit their flexibility.

- Cycloid scales: trout, salmon, and sardines have these smooth, thin, round scales with growth rings. They give fish a good balance of protection and swimming ability.

- Ctenoid scales: these are like cycloid scales but have tiny spines on their back edge. Perch, bass, and similar fish have these scales. If you run your hand from a fish's tail to its head, you can feel these spines.

Did you know that by 2050, there could be more artificial debris than fish in our oceans? Learn about this critical environmental challenge in our marine conservation article.

If you want to read similar articles to Parts of a Fish Explained, we recommend you visit our Facts about animals category.

- Agresti, M. (2024, March 18). Fish anatomy: Internal & external diagrams. N1 Outdoors. https://n1outdoors.com/fish-anatomy/

- Australian Museum. (n.d.). Fish scales. https://australian.museum/learn/animals/fishes/fish-scales/

- Bjørgen, H., & Koppang, E. O. (2021). Anatomy of teleost fish immune structures and organs. Immunogenetics, 73(1), 53-63. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00251-020-01196-0

- BYJUS. (2020, December 7). Respiration in fish. https://byjus.com/biology/respiration-fish-mechanism/

- Center for Biological Diversity. (n.d.). Ocean plastics pollution. https://www.biologicaldiversity.org/campaigns/ocean_plastics/