Rules of Thermoregulation in Animals

Nature is full of remarkable adaptations, and thermoregulation is no exception. This section will explore three fascinating ecogeographical principles: Bergmann's rule, Allen's rule, and Gloger's rule. These principles reveal intriguing patterns in how body size, appendages, and pigmentation influence an animal's ability to manage heat in different climates.

In the following article by thedailyECO, we explore what the rules of thermoregulation in animals are, explaining Bergmann's, Allen's, and Gloger's rules – key principles that influence how animals manage their body temperature.

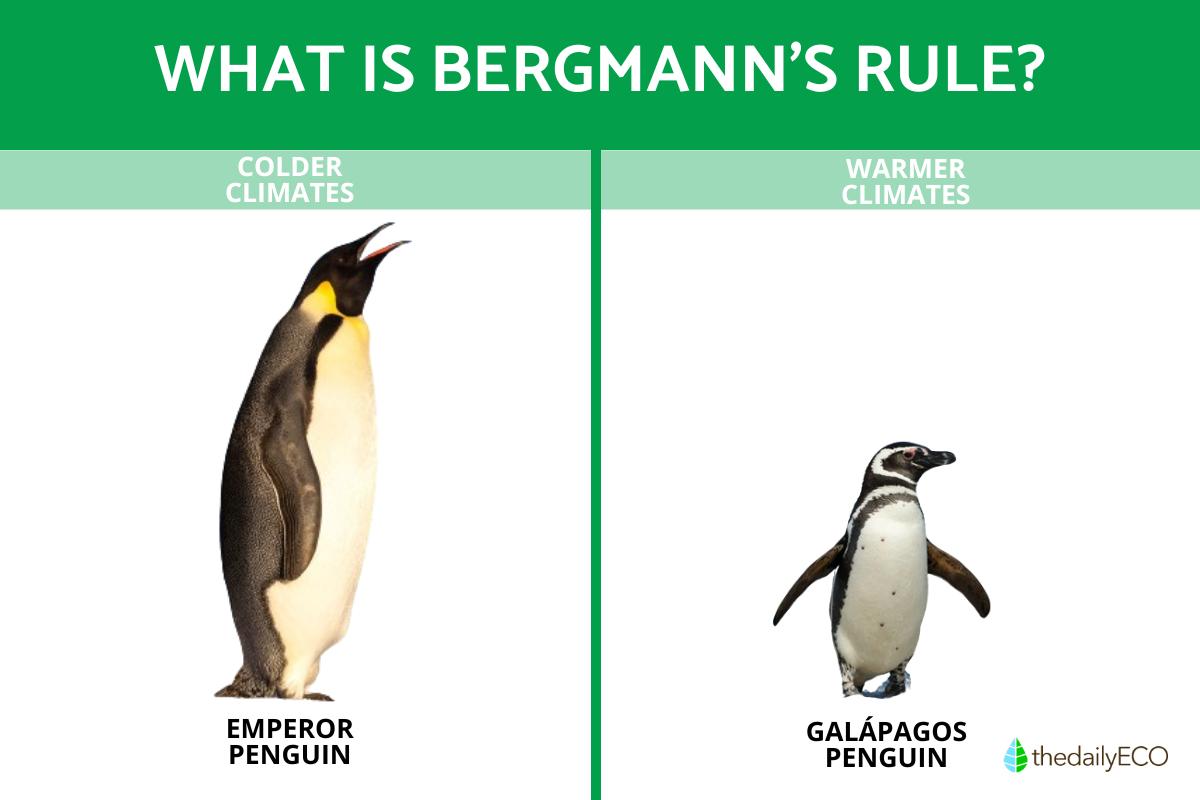

What is Bergmann's rule?

Bergmann's rule, named after biologist Carl Bergmann, describes a fascinating pattern in warm-blooded animals (endotherms). Across a species or closely related groups, individuals tend to be larger in colder environments and smaller in warmer ones.

This size difference is all about heat regulation. In other words, it is a matter of life and death for endotherms who must maintain a constant internal temperature.

The key lies in surface area to volume ratio. Larger bodies, like polar bears, have a smaller surface area relative to their volume. This means they lose heat to the colder environment at a slower rate, helping them conserve precious body warmth. Conversely, smaller animals, like desert foxes, have a larger surface area relative to volume. This allows them to dissipate heat more efficiently in hot environments, preventing them from overheating.

Bergmann's rule isn't a rigid law, though. Exceptions exist. For instance, some aquatic mammals may defy the trend due to the insulating properties of water. Additionally, factors beyond temperature, like food availability, can influence body size in some species.

To illustrate Bergmann's rule, let's look at some real-world examples:

- Squid: Colossal squid, inhabiting deep-sea environments with temperatures around 0°C (32°F), can reach lengths of 15 meters (49 feet). Conversely, reef squid dwelling in warmer tropical and temperate waters are significantly smaller, typically ranging from 3 to 30 centimeters (1 to 12 inches).

- Penguins: Emperor penguins, the largest penguin species, reside in Antarctica's frigid climate. Their large size, reaching around 120 centimeters (3.9 feet) in height, may be advantageous for heat conservation. The Galapagos penguin, found in milder temperatures, is a smaller species, measuring around 50 centimeters (1.6 feet).

- Brown Bears: Geographic location influences brown bear size. Larger brown bears are found in colder regions like Alaska and Siberia, while smaller brown bears inhabit warmer regions like the American Southwest or Europe.

- Wolves: Similar trends are observed in wolves. Canadian and northern European wolves, dwelling in colder climates, are generally larger than their southern counterparts found in the United States or India.

Have you ever wondered how animals in different parts of the world can evolve similar traits? This is called parallel evolution, and you can learn more about it in this other article.

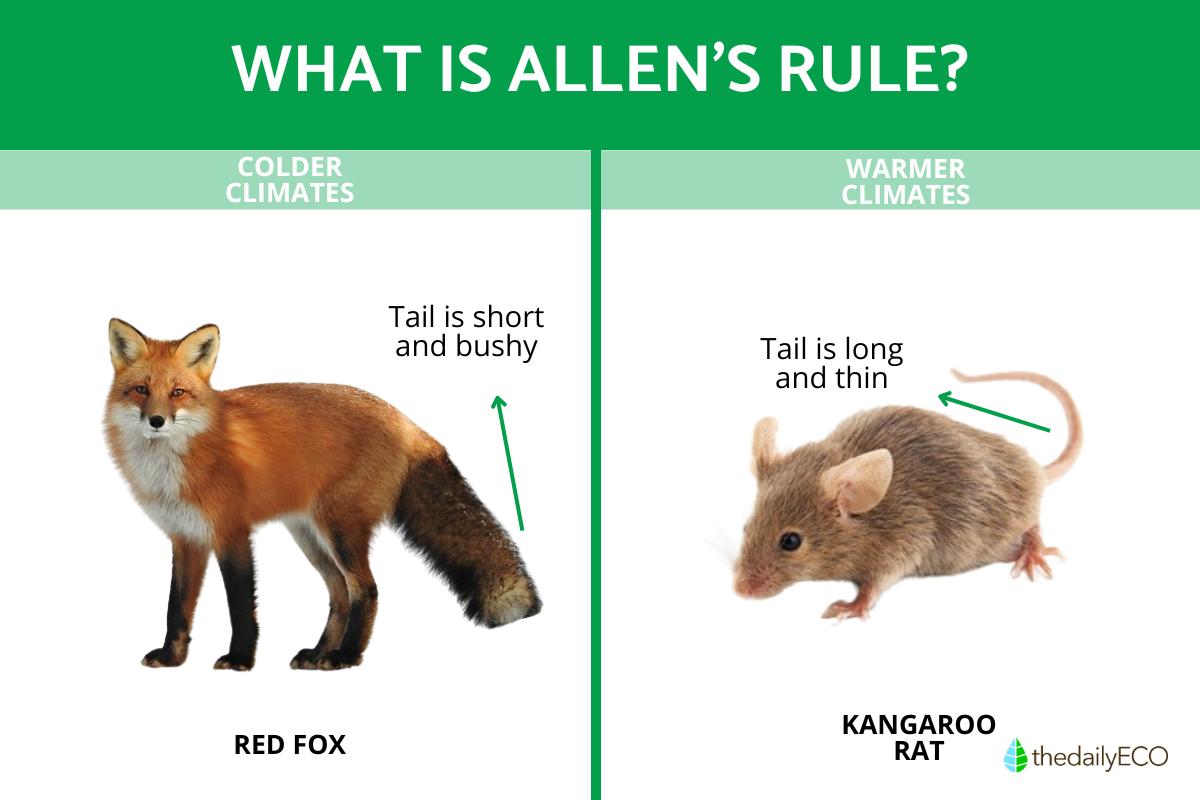

What is Allen's rule?

Allen's rule, formulated by Joel Asaph Allen in 1877, complements Bergmann's rule by addressing appendage size in warm-blooded animals. Unlike Bergmann's rule, which focuses on overall body size, Allen's rule emphasizes the correlation between ambient temperature and the size of body appendages such as ears, tails, and limbs.

Put simply, Allen's rule suggests that endotherms living in colder climates tend to have shorter extremities relative to their body size compared to those in warmer climates. This adaptation aids in heat retention in colder environments, where minimizing heat loss is crucial for maintaining a constant internal temperature.

Conversely, in warmer climates, the priority shifts to dissipating excess heat. Accordingly, endotherms in warmer environments tend to have longer appendages, which offer a larger surface area to volume ratio for enhanced heat dissipation. Thus, Allen's rule underscores how variations in appendage size among warm-blooded animals reflect adaptations to regulate body temperature in different environmental conditions.

Some examples include:

- Ears: fennec foxes of the Sahara desert possess large, well-vascularized ears, aiding in heat dissipation. Conversely, arctic foxes have smaller ears to minimize heat loss.

- Limbs: arctic foxes have short, stout limbs to conserve heat, while long-legged antelopes dwelling in hot savannas can dissipate heat more efficiently through their limbs.

- Tails: some desert rodents, like kangaroo rats, have long, thin tails that promote heat loss. However, some cold-adapted animals, like arctic foxes, have bushy tails that provide insulation.

It's important to note that Allen's rule is a general trend, and exceptions exist. Other factors, such as insulation (fur, fat) and behavior (basking, burrowing), also play a role in thermoregulation.

What is Gloger's rule?

Animals' pigmentation can also be influenced by environmental factors such as temperature and sunlight exposure. This is known as Gloger's rule, formulated by the German ornithologist Constantin Wilhelm Lambert Gloger in 1833.

It states that in warm and humid areas, darker pigmentation is often observed, while lighter tones prevail in drier and colder environments. This adaptation aids in thermoregulation, as darker pigmentation absorbs more heat, beneficial in cooler climates but potentially leading to overheating in warmer regions.

A well-known example of this adaptation is seen in bears. The polar bear (Ursus maritimus) exhibits white fur, blending with its snowy habitat and aiding in hunting. In contrast, the brown bear (Ursus arctos), inhabiting less snowy regions, typically has brown fur.

In mammals, pigmentation, particularly melanin, serves to protect against UV radiation and regulate body temperature. Dark pigmentation can absorb more UV radiation, providing protection against its harmful effects. Similarly, in birds, pigmentation plays a role in thermoregulation and UV protection. Dark feathers may resist bacterial growth better than lighter ones, contributing to overall health and survival.

Did you know that some closely related species can take wildly different evolutionary paths? Discover the fascinating concept of divergent evolution in this article.

If you want to read similar articles to Rules of Thermoregulation in Animals, we recommend you visit our Biology category.

- Escolásico León, C., Claramunt Vallespí, T. (2013). ECOLOGY I: INTRODUCTION. ORGANISMS AND POPULATIONS. Spain: UNED.