What Are Ctenophores? A Guide to Comb Jellies

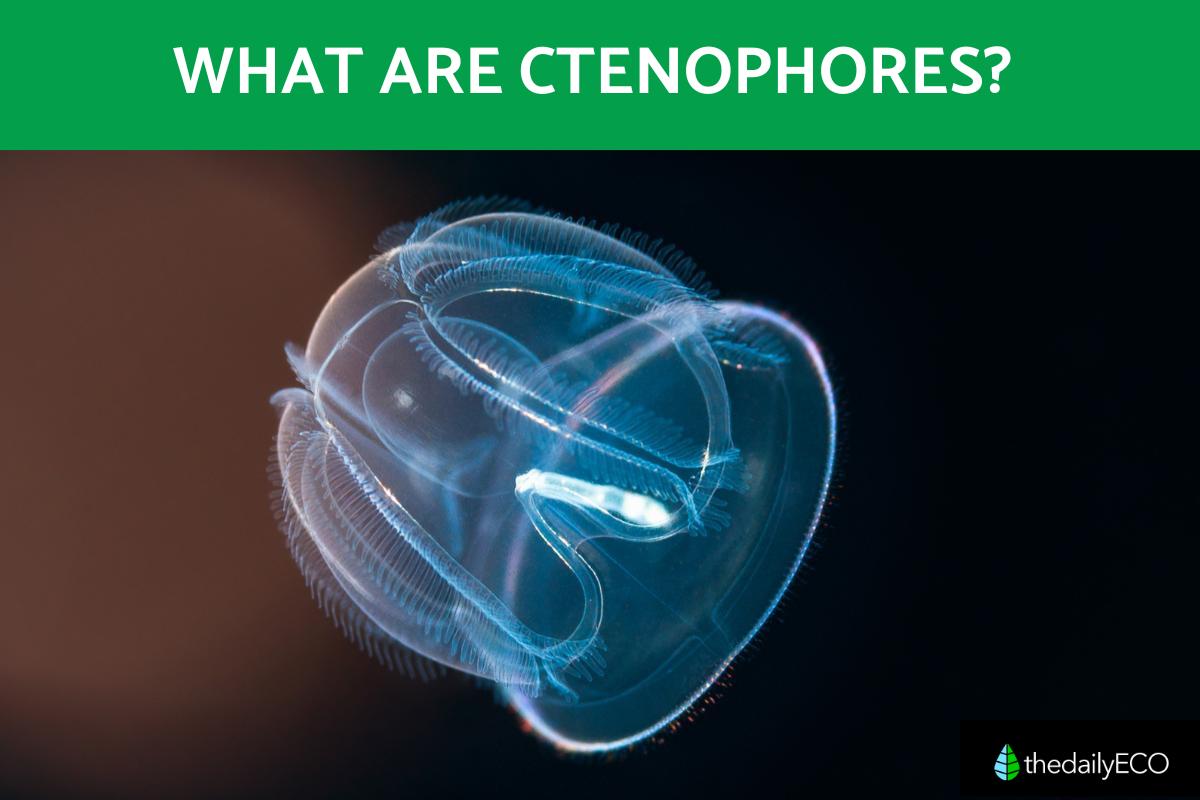

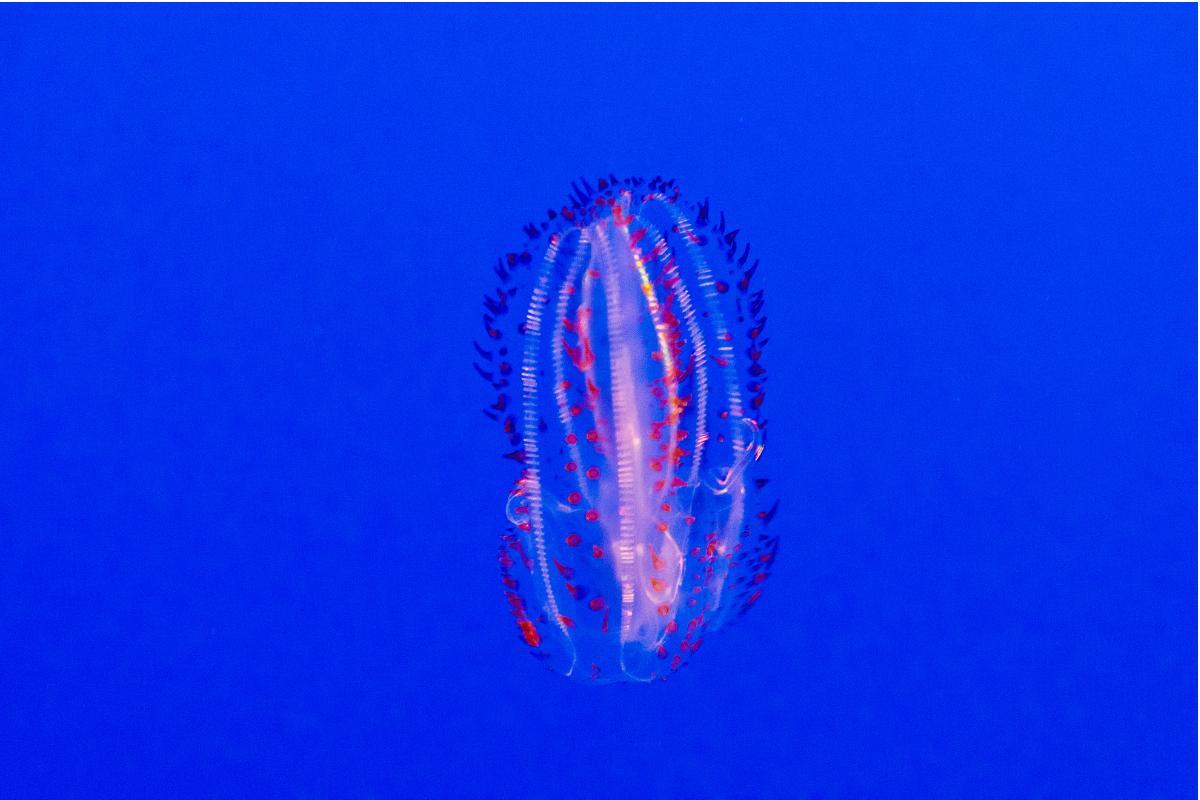

Ctenophores, commonly known as comb jellies, are marine invertebrates that, despite their jelly-like appearance, they are distinct from jellyfish. They belong to their own unique phylum, Ctenophora. Characterized by rows of cilia, or comb-like structures, these creatures use these for movement, creating a mesmerizing rainbow effect as light diffracts through them. Found in oceans worldwide, ctenophores play an important role in marine ecosystems.

This article by thedailyECO will explore what ctenophores are, their defining characteristics, and some intriguing examples that highlight their diversity.

What are ctenophores?

Ctenophores, commonly known as comb jellies, are marine organisms characterized by their gelatinous bodies and planktonic lifestyle.

Their name, derived from the Greek word ktenos, meaning "comb bearer," reflects the eight rows of cilia, or "ctenes," that they possess. These cilia function like combs, allowing them to propel themselves through the water with a graceful, shimmering motion.

The phylum Ctenophora encompasses over 200 species, which inhabit oceans worldwide, from shallow coastal waters to the depths of the open sea. They play a significant role in the marine ecosystem, representing a substantial portion of the planktonic biomass. Ctenophores exhibit a wide range of sizes; some species are as small as a few centimeters, while others can grow to impressive lengths of up to 2 meters or more (approximately 6.5 feet).

Despite having a sparse fossil record due to their soft bodies, ctenophores have a long evolutionary history. Fossil evidence suggests that ctenophore-like organisms existed during the Cambrian period, approximately 500 million years ago, indicating their early emergence in the marine environment. This evolutionary lineage highlights their adaptability and resilience in diverse ocean habitats.

Characteristics of ctenophores

- Ctenophores possess a diploblastic structure, meaning they develop from two embryonic layers: the ectoderm and endoderm, with a gelatinous substance known as mesoglea situated between them. This organization is a common feature among simpler animal forms.

- They are classified as acoelomates, which means they lack a true body cavity. Instead, their body structure consists of the gastrovascular cavity, which serves multiple functions including digestion and circulation.

- Ctenophores exhibit radial symmetry, allowing their body structure to be divided along multiple planes. This symmetry is typical of many aquatic organisms, enabling them to respond to environmental stimuli from all directions.

- They demonstrate a tissue level of organization, consisting of various specialized cell types that work together to perform specific functions. This organization is more advanced than that of simpler organisms like sponges.

- Ctenophores use eight rows of ciliated comb plates, called ctenes, which are their primary locomotion organs. These cilia beat in a coordinated fashion, propelling the animals through the water.

- The size of ctenophores varies greatly, with species measuring anywhere from 1 mm to 1.5 meters in length, showcasing considerable diversity in their morphology.

- They have specialized cells called coloblasts in their tentacles, which function similarly to the cnidoblasts found in cnidarians (like jellyfish) but do not possess stinging capabilities. Coloblasts are adhesive cells that help capture prey.

- The outer epidermis of ctenophores contains sensory cells that secrete mucus for protection and aid in prey capture, enhancing their ability to interact with their environment.

- Ctenophores lack a centralized brain and central nervous system. Instead, they have a nerve net surrounding the oral region, which coordinates their movements and responses to stimuli.

- Their internal cavity includes the mouth, pharynx, and various ducts lined with gastrodermis, facilitating digestion and nutrient absorption.

- Many ctenophores are capable of bioluminescence, producing light through chemical reactions. This ability creates stunning visual effects in the water and can serve as a mechanism for communication or deterring predators.

- Ctenophores possess remarkable regenerative abilities, allowing them to repair and regenerate damaged tissues, which enhances their survival in the wild.

- Ctenophores often form large aggregations, which can be beneficial for feeding, defense, and reproduction.

If you’re fascinated by the magic of marine life, discover how some shores light up at night with a natural glow.

How do ctenophores eat?

All ctenophores are carnivorous, feeding primarily on a variety of small marine organisms, including:

- Rotifers and cmall crustaceans: they often consume tiny crustaceans such as copepods, amphipods, and euphausiids (krill), which form a substantial part of their diet.

- Planktonic larvae: they prey on the larvae of many marine species, including mollusks and gastropods (snails), contributing to their role as predators in the planktonic food web.

- Other ctenophores: some species, particularly those from the Beroida order, like Beroe, are specialized predators of other ctenophores, using their large mouths to engulf their prey.

Ctenophores utilize different strategies for capturing prey, depending on their species and anatomy:

- Many ctenophores capture prey with long tentacles that are coated in mucus, trapping small organisms as they drift by.

- Colloblasts are unique, sticky cells found on their tentacles that help ensnare prey. Unlike the stinging cells of cnidarians (nematocysts), colloblasts do not sting but stick to prey.

- Interestingly, some ctenophore species, such as those from the genus Haeckelia, capture nematocysts (stinging cells) from their cnidarian prey and incorporate them into their own tentacles for defense and prey capture.

- Species like Euplokamis have prehensile lateral branches on their tentacles, which they use to grasp and trap their prey efficiently.

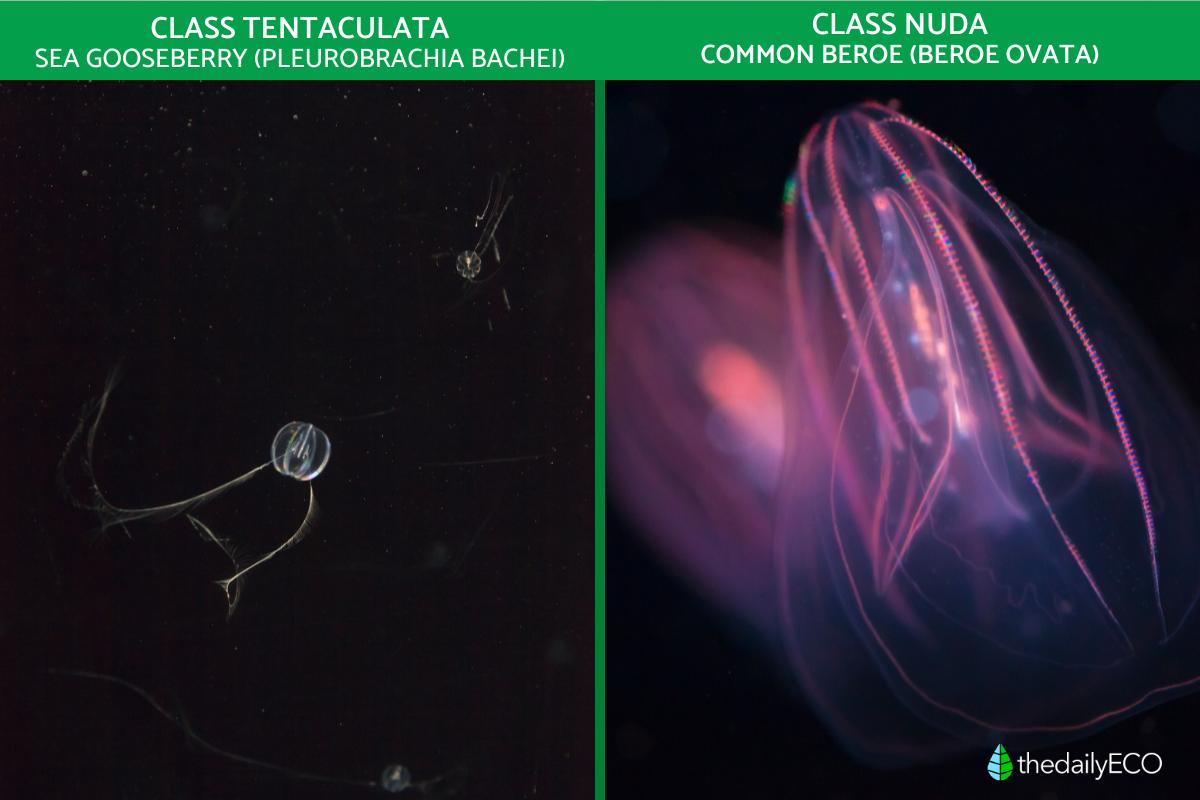

Ctenophores are generally divided into two primary classes based on their dietary habits and anatomy:

- Tentaculata: this class includes species with tentacles, such as the sea walnut (Mnemiopsis leidyi). These species capture prey like larval mollusks and copepods using their long tentacles.

- Nuda: members of this class, like Beroe, lack tentacles altogether. Instead, they rely on their large mouths to feed on other gelatinous zooplankton, including jellyfish and other ctenophores.

How do ctenophores reproduce?

Most ctenophores reproduce sexually, going through two stages: a larval stage and an adult stage.

In some species, like tentacled and lobed cydippids, reproduction can occur even before they are fully grown. This early form of reproduction is called dysogeny. However, not all ctenophores follow this pattern. For example, Mnemiopsis leidyi starts reproducing when it's still very small and continues to spawn regularly when conditions like food supply and temperature are favorable.

Most ctenophores are simultaneous hermaphrodites, meaning they have both male and female reproductive organs and can produce both eggs and sperm at the same time. This gives them an advantage in environments where finding a mate might be difficult. In some species, however, individuals are either male or female (dioecious species).

In a few ctenophores, especially those in the order Platyctenida, asexual reproduction is also possible. These species can reproduce through fragmentation, where a piece of their body can grow into a whole new individual. This helps them recover their population quickly if needed.

Ctenophores produce reproductive cells, called gametes, in their gastrovascular canals. These gametes are released through the mouth, and fertilization typically happens externally in the water, meaning the eggs and sperm mix in the surrounding environment. This process is common in marine animals and helps increase genetic diversity.

Ctenophores can produce gametes daily when conditions are good, though reproduction slows down when food is scarce. Once they release the gametes, they don’t provide any care for the offspring. The fertilized eggs are left to develop on their own, without any parental involvement.

Examples of ctenophores

Ctenophores, or comb jellies, are categorized into two major classes:

Class Tentaculata:

This class includes ctenophores that possess tentacles, which they use to capture prey. Many species within this class are planktonic and can be found in a variety of marine environments. Some well-known species include:

- Sea Gooseberry (Pleurobrachia bachei): this ctenophore is commonly found in coastal waters and is recognized for its spherical body and long, branched tentacles used for prey capture.

- Venus' Girdle (Cestum veneris): known for its ribbon-like shape, this ctenophore is notable for its size and elegant swimming style. It is often found in open ocean environments.

- Comb Jelly (Euplokamis crinita): this species inhabits deep-sea environments and features prehensile lateral branches that assist in capturing prey.

- Sea Walnut (Bolinopsis microptera): a widely distributed ctenophore found in the open ocean, recognized for its gelatinous body and the ability to swim using its ciliated comb rows.

- Antarctic Comb Jelly (Callianira antarctica): this species is adapted to cold Antarctic waters and contributes to the unique biodiversity of these regions.

Class Nuda:

Unlike Tentaculata, members of this class lack tentacles. They typically capture prey by engulfing them with their large mouths, and primarily feed on other ctenophores and gelatinous organisms.

- Common Beroe (Beroe ovata): a large, cylindrical ctenophore that feeds on other gelatinous animals like Mnemiopsis leidyi. Found in temperate and subtropical waters.

- Cucumber Beroe (Beroe cucumis): a transparent, cylindrical species commonly found in various oceans. It is an active predator of other ctenophores, particularly in colder waters.

- Forskal's Beroe (Beroe forskalii): this species is found in warm marine waters and also preys on gelatinous organisms like other ctenophores.

From the depths of the ocean to your screen, explore how these luminous creatures shine in the dark and the science behind their glow.

If you want to read similar articles to What Are Ctenophores? A Guide to Comb Jellies, we recommend you visit our Biology category.

[National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA)](https://oceanservice.noaa.gov/facts/ctenophores.html)

- Madinand, L. and Harbinson, G. (2008). Gelatinous Zooplankton. Encyclopedia of Ocean Sciences (Second Edition). Pages 9-19. Available at: https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/agricultural-and-biological-sciences/ctenophora

- Allison Edgar, Ponciano, J., and Martindale, M. (2022). Ctenophores are direct developers that reproduce continuously beginning very early after hatching. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2122052119

- Neupane, L. (2023). Phylum Ctenophora. Microbenotes. Available at: https://microbenotes.com/phylum-ctenophora/

[University of California Museum of Paleontology](https://ucmp.berkeley.edu/arthropoda/cteno.html)

- [National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA)(https://oceanservice.noaa.gov/facts/ctenophores.html)

- [Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology on Bioluminescence](https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fbioe.2020.00063/full)